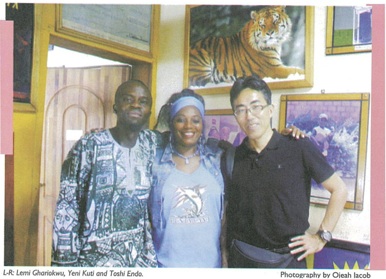

I was surpised to find that Nigeria produces so much rich music -- Tosihya Endo

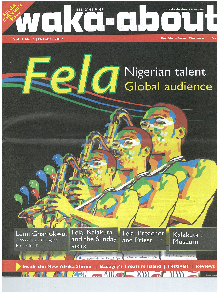

Interview by Pelu Awofeso (appeared in Waka-about Vol. 2, Issue 6, p14 and p22 (2012))

It’s amazing that a Japanese academic is so knowledgeable in African music. How did it all begin?

In the 1970s, my interest was in American folk and pop music, the singer-writer kind of music. But then all of a sudden, some great music started to come from the developing world, which had a huge impact on me. That was Bob Marley. What he sang about was reality, different from the songs American used to do. So I was stunned that the kind of music could come from the peripheral of the world, Jamaica. Needless to say that I was impressed by this fact, so I looked for other music in a similar context, and I came across music from Africa, especially in Nigeria. I discovered Fela Kuti/Afrobeat, Sunny Ade/Juju music. I was surprised that such rich music was produced in Nigeria. More and more, I went deeply into Nigerian music.

You didn’t just limit your interest to listening and enjoying the songs; you actually created a blog, a very rich discography of African music. What was the motivation for that?

African music was difficult to find in Japan. It is also difficult to get vinyl records of music made in Nigeria. The only way for me to do it was to contact record shops in London. There was a particular one called the Stern’s Radio (at the time), which was exclusively into Nigerian music. I used the mail order system of the record shop to get Nigerian music. I did that over time and my collection increased year after year. Still my collection was very limited, and as things would happen I had the opportunity to visit Nigeria in 1980 and I collected a lot of music. Still they weren’t enough, so I collected more and more. Then I thought it was important to make those pieces of collected information accessible to public, to everybody. So I decided to start a website, the discography that you referred to, at the onset of Internet in the 1990s. I the beginning, I just gathered information from my personal collection and uploaded them on the site; but then many people all over the world contacted me and started to tell me what was missing, and some even helped me to fill in the gaps. The database expanded and has been expanding ever since.

As they say, music is a universal language. But when you listen to African music that you have, are you able to understand the message in the songs?

To tell the truth, I don’t understand the African language and I don’t understand the message in the music. But I try to learn what the message is because I am also very interested in what the message really is. I understand that Juju music has this kind of message, same for Fuji, same for Afro-beat and so on. But then you must know that music is not just about the lyrics; it is a total entity, a combination of sound, beats and of course, lyrics. This, I think, is sufficient for me to understand the groove.

You have visited the New African Shrine, built by Femi, Fela’s son. What did you feel being in the hall?

When I came to Nigeria in 1980, I wanted to see a live performance by Fela but at that time he was in Italy, so I couldn’t and it was painful for me. Then he passed away and I had no chance to see his live show. But now, I know that his children are doing very well in music and transforming Afro-beat in their own way, and they have provided a venue for live performance. This is very impressive and I was very happy to be there to see how popular the place is.

In collecting all of this music across Africa, it’s like a service to humanity and to Africa in particular. Is it that Africa is unable to preserve its own unique heritage by itself?

This is a pity. There is so much treasure in African culture and much nice music has been produced in the past 30-40 years. But they are all in vinyl records and most of them have been lost in Nigeria but kept in countries in Europe and Asia (Japan). Virtually, nothing remains here. It is really a pity. I realize that nearly nobody in Nigeria cares about the value of this important heritage. But this is understandable for me, in a sense, because young people are interested in other things and most are not interested in collecting mere records, when there is need for survival and the governments need to invest in infrastructure. We are just collectors and outsiders. Sad that a lot of treasure is lost in Africa, but all the same we can share the value of African heritage.

What do you do with your actual collection in Japan – are you planning for an exhibition some day?

For example most of Fela’s recordings are virtually non-existent in Nigeria and only a few of these can be found elsewhere in the world. So I collected those recordings from many collectors everywhere I could find them abroad, I edited them and the list is updated. I released a set of three CDs of his music; I am doing this as some form of payback for Fela’s fans with the help of record collectors all over the world, and several collectors are dong same with different kinds of global music.

Will I be right to say that you have more interest in Fela and Afro-beat than in other genres of Afro-beat?

No, no, no. I love all the music equally. I love Afro-beat, Juju, Fuji, Sakara, Apara, Waka and highlife – I love all the Yoruba and Ibo music. They all have special attraction for me.

You have just recently been to Kinshasa. What was it like in that part of Africa?

Kinshasa is rich in Rumba-rock music, a huge category of African music that can compete fairly well with Nigerian and West Africa music like the Senegalese music. Rumba-rock stems from Cuban music imported to then Zaire long time ago. That brand of music has been transformed by the likes of Papa Wemba and some others. So it has a long history, just like Nigerian music, which had its beginnings in what has been called ‘Palm wine music’. Rumba-rock has excellent in vocal harmony with guitar and percussion instruments. In Yoruba music, we have nice talking drums and beats. Each musical genre has its own character and attractiveness. It will be difficult to say one is better than the other. Sometime ago many Congolese musicians left their country because of all the strife and fled abroad to France, Belgium etc. in Europe in very large number. Now, they are all coming back and they are very active in music.